Indians Knew the Earth Was Round Long Before the Greeks

Indians Knew the Earth Was Round Long Before the Greeks

For centuries, the dominant narrative in global historiography has credited ancient Greece with the first scientific recognition of Earth’s spherical shape. Figures like Pythagoras, Aristotle, and Eratosthenes are often cited as pioneers of this idea. But what if this understanding existed in India long before it echoed through the halls of Athens?

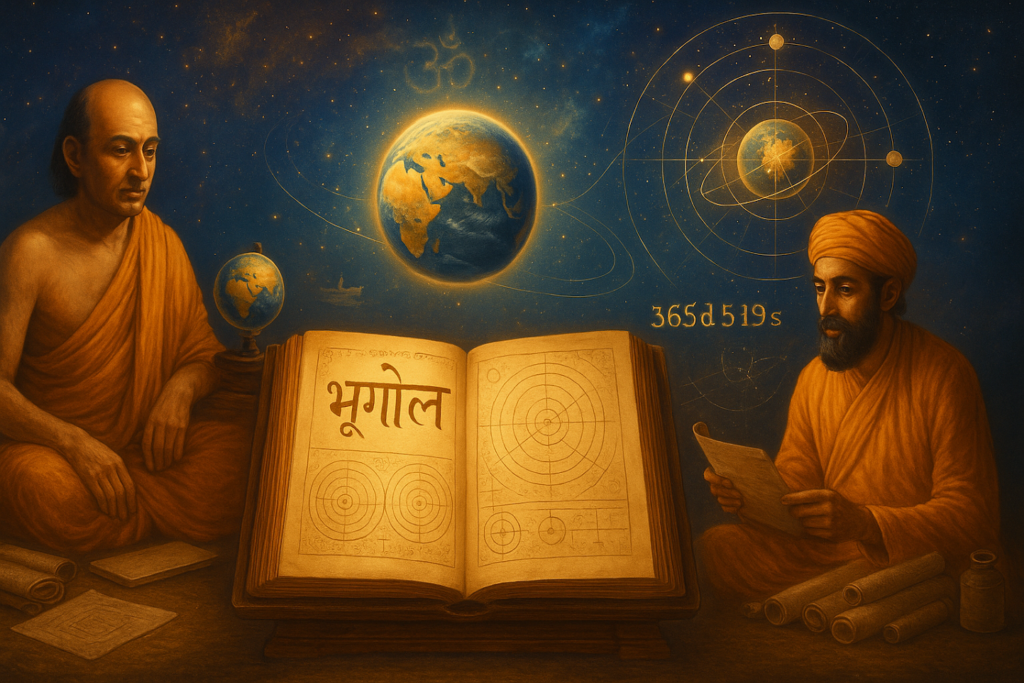

The very word Bhugola—used in ancient Indian texts—offers a clue. Bhu means Earth, and Gola means sphere. This isn’t poetic metaphor; it’s a precise cosmological term. Ancient Indian astronomers didn’t just speculate about the Earth’s shape—they embedded it in their mathematical models, astronomical calculations, and spiritual cosmology.

In 499 CE, Aryabhata composed the Aryabhatiya, a seminal work in Indian astronomy. He proposed that the Earth rotates on its axis, explaining the apparent movement of stars as an illusion caused by Earth’s motion. He used the analogy of a person in a moving boat perceiving stationary objects as moving backward—a remarkably intuitive explanation.

Aryabhata’s model didn’t just suggest rotation—it implied sphericity. A rotating flat Earth would produce observational inconsistencies. His calculations of planetary positions and eclipses were so accurate that centuries later, French astronomer Guillaume Le Gentil found Indian predictions more precise than European ones during a lunar eclipse.

Brahmagupta, another towering figure in Indian science, lived in the 7th century CE. He not only introduced the concept of zero but also argued that the Earth was round. His treatise Brahmasphutasiddhanta contains over 1000 verses covering algebra, geometry, and astronomy. He calculated the length of the solar year with astonishing precision—365 days, 5 minutes, and 19 seconds.

Brahmagupta’s cosmology was deeply mathematical. He didn’t rely on telescopes or instruments—just logic, observation, and calculation. His understanding of planetary motion and eclipses required a spherical Earth model to make sense.

Even earlier, Vedic literature and Puranic texts hinted at a spherical Earth. The Surya Siddhanta, a foundational astronomical text, describes Earth as a globe suspended in space. It outlines planetary motions, eclipses, and time cycles with remarkable sophistication.

The Rigveda and Atharvaveda contain hymns that describe the Earth as floating in space, held by cosmic forces. While these may be poetic, they reflect a worldview that transcends flat-Earth assumptions.

Ancient Indian astronomers used shadow measurements, star inclinations, and eclipse timings to infer Earth’s curvature. By comparing the length of shadows at different latitudes, they could deduce that the Earth wasn’t flat. These methods mirror those used by Eratosthenes in Greece—but may have predated him.

Some historians argue that Indian knowledge of Earth’s shape came through Hellenistic influence after Alexander’s campaigns. But this view underestimates India’s indigenous scientific tradition. The depth and originality of texts like Aryabhatiya and Brahmasphutasiddhanta suggest independent development.

Moreover, India’s astronomical schools—like those in Ujjain and Bhinmal—were thriving centers of learning long before Greek contact. The precision of their models and the philosophical depth of their cosmology point to a native tradition of inquiry.

In Indian thought, cosmology wasn’t just about physical models—it was intertwined with metaphysics. The spherical Earth was part of a larger vision of cyclical time, cosmic balance, and spiritual evolution. The Earth wasn’t merely a planet—it was a living entity, a manifestation of Prakriti.

This symbolic resonance is reflected in temple architecture, ritual calendars, and even yantras. The Shri Yantra, for example, encodes cosmic geometry that mirrors planetary motion and spatial harmony.

Reclaiming India’s scientific legacy isn’t about nationalism—it’s about restoring balance to global narratives. When we acknowledge that ancient Indians understood Earth’s shape long before it became Western orthodoxy, we honor a tradition of inquiry that was both rigorous and poetic.

It also challenges the myth that science and spirituality are incompatible. In India, they danced together—producing insights that were both mathematically precise and spiritually profound.